First, the guide. An annual tradition, the Make: Boards Guide is a pull-out which aims to serve as an at-a-glance reference for the most popular, interesting, well-established, or increasingly simply “in-stock” development boards. It covers microcontroller boards, single-board computers, and field-programmable gate array (FPGA) boards – and, this year, sees a major refresh with some long-established entries being dropped either as a result of ongoing availability problems or their manufacturers’ choosing to discontinue the parts.

In addition to the pull-out, I contributed an article which takes a look at the ongoing supply chain issues in the electronics industry from a different perspective: how good it’s been for two companies able to fill in the gaps in their competitors’ product lines, Espressif and Raspberry Pi. I’d also like to offer my thanks to Eben Upton for taking the time to talk to me on the topic.

Espressif, in fact, forms a central pillar in my second feature for the issue: the rise of the free and open-source RISC-V architecture in the maker sector. Espressif was one of the first big-name companies to offer a mainstream RISC-V part, and has since announced it will be using RISC-V cores exclusively – and it’s no surprise to see others in the industry taking note. The feature walks through a brief history of the architecture, its rivals, and brings arguments both for and against its broad adoption in a market all-but dominated by Arm’s proprietary offerings. As always, thanks go to all those who spoke to me for the piece.

Make: Magazine Volume 83 is available now at all good newsagents or digitally as a DRM-free PDF download on the Maker Shed website.

This month’s Hobby Tech column features my field report from the Maker Faire UK 2016 event, an interview with my good friend Daniel Bailey about his brilliant homebrew computers, and a review of the Genuino MKR1000 microcontroller.

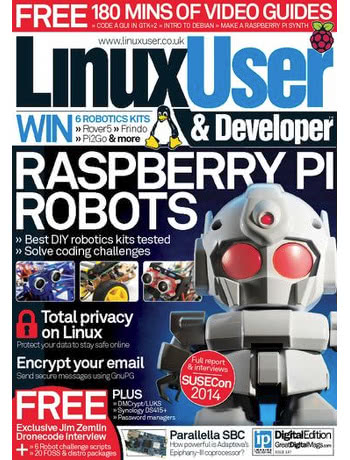

This month’s Hobby Tech column features my field report from the Maker Faire UK 2016 event, an interview with my good friend Daniel Bailey about his brilliant homebrew computers, and a review of the Genuino MKR1000 microcontroller. This month’s Linux User & Developer magazine includes my review of a device I’ve been wanting to play with ever since I first interviewed its creator, Andreas Olofsson: the Adapteva Parallella.

This month’s Linux User & Developer magazine includes my review of a device I’ve been wanting to play with ever since I first interviewed its creator, Andreas Olofsson: the Adapteva Parallella.