Powered by a field-programmable gate array (FPGA), giving it the ability to transform into anything from a BBC Micro to a Galaxians arcade cabinet, the ZX Spectrum Next is around two years past its original launch schedule. The delay has been attributed to getting everything right, in particular the Rick Dickinson-designed chassis and keyboard – and, in TBBlue’s defence, the entire package is undeniably impressive.

For PC Pro’s testing I went hands-on with a production model of the top-end variant, the ZX Spectrum Next Accelerated. This features 1MB of memory upgradeable to 2MB, which is a lot if you’re thinking in 1980s terms, with a pre-fitted real-time clock and Wi-Fi module to match the mid-range Plus model. The stand-out feature of the Accelerated version, though, is a Raspberry Pi Zero fitted internally to act as a coprocessor – a concept gently borrowed from the BBC Micro and its Tube socket, to which the world’s first Arm processors were connected.

It wasn’t my first experience with the ZX Spectrum Next: I reviewed an early revision of the motherboard, minus case and keyboard, two years ago. In that time, though, the company and the community behind the project have worked to really polish things up: there’s a wire-bound printed manual, though sadly lacking an index; the operating system is swish and the bundled games impressive; the lost 28MHz ultra-fast accelerated operation mode is back, after being dropped in favour of a 14MHz mode following timing issues with the RAM; and while some features aren’t quite ready, in particular the ability to load multiple FPGA cores into a menu and choose from them at boot-up, it’s already a device that will appeal to vintage computing enthusiasts.

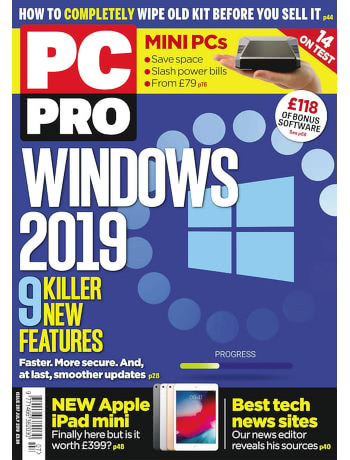

The full review is available now in PC Pro Issue 309, available at your nearest stockists or online in print or digital formats.

This month’s PC Pro includes a review of something a little out of the ordinary: the open-source, microcontroller-powered OpenScope MZ oscilloscope from Digilent.

This month’s PC Pro includes a review of something a little out of the ordinary: the open-source, microcontroller-powered OpenScope MZ oscilloscope from Digilent. This month’s issue of PC Pro includes a four-way Battle Royale of DIY handheld games consoles, starting with the

This month’s issue of PC Pro includes a four-way Battle Royale of DIY handheld games consoles, starting with the

In this month’s PC Pro I turn my eye to the

In this month’s PC Pro I turn my eye to the