First, the Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+. As the name suggests, the new board isn’t quite a full generation above the existing Raspberry Pi 3 Model B. It is, however, a considerable upgrade – primarily thanks to a new packaging for the BCM2837 system-on-chip, now known as the BCM2837B0, which vastly improves its thermal performance and boosts its speed from 1.2GHz to 1.4GHz. Elsewhere, the board includes an upgraded and simplified power supply system, gigabit Ethernet – though limited to around 230Mb/s throughput in real-world terms – and dual-band 802.11ac wireless network capabilities. Naturally, the review also includes thermal imaging analysis – this time using a new overlay technique which, I’m pleased to say, offers a significant improvement in image clarity over my previous approaches.

The Gamebuino Meta, on the other hand, is a very different device to its predecessor. Upgraded from an ATmega microcontroller to an Arm chip, the Gamebuino Meta boasts a colour screen, programmable RGB LED lighting, a general-purpose input/output (GPIO) header with ‘developer backpack’ accessory for easy prototyping – in short, it’s a serious upgrade over the device I reviewed back in Issue 134. Despite the upgrades, though, it’s still extremely accessible, allowing users to write their own games using the Arduino IDE and the Gamebuino library with ease.

Finally, Arduino Create. I’ve been meaning to take a look at the cloud-based development environment for a while, but it wasn’t until it added support for single-board computers like the Raspberry Pi – on top of the Arduino boards it already supported – that I found an excuse to dive in. What I found is somewhat rough around the edges, but shows promise: a fully-functional IDE right in the browser, but with the ability to push sketches – with very little modification for the Raspberry Pi – to devices remotely.

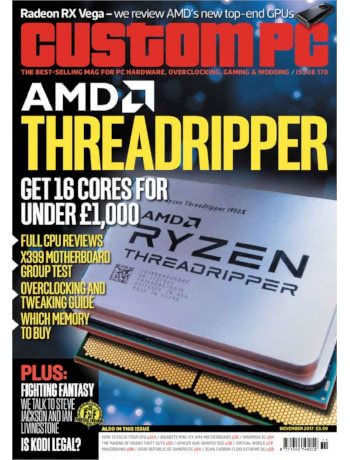

All this, plus the usual raft of things I didn’t write, can be found between the crisp paper covers of Custom PC Issue 178 at your nearest supermarket, newsagent, or electronically via Zinio and similar digital distribution services.

This month’s Custom PC magazine has a bumper crop for fans of Hobby Tech: a four-page shoot-out of do-it-yourself handheld games consoles on top of my usual five-page column, which this time around looks at setting up

This month’s Custom PC magazine has a bumper crop for fans of Hobby Tech: a four-page shoot-out of do-it-yourself handheld games consoles on top of my usual five-page column, which this time around looks at setting up  This month’s issue of PC Pro includes a four-way Battle Royale of DIY handheld games consoles, starting with the

This month’s issue of PC Pro includes a four-way Battle Royale of DIY handheld games consoles, starting with the  This month’s Hobby Tech column has a particular focus on do-it-yourself handheld gaming, looking at two Arduino-compatible yet totally different kits: the

This month’s Hobby Tech column has a particular focus on do-it-yourself handheld gaming, looking at two Arduino-compatible yet totally different kits: the  In Hobby Tech this month I take a look at the new Raspberry Pi-based

In Hobby Tech this month I take a look at the new Raspberry Pi-based