Starting with the game first, Exapunks caught my eye as soon as I saw it announced by developer Zachtronics. Taking the assembler programming concept of earlier titles TIS-100 and Shenzhen-IO, Exapunks wraps them up in a 90s near-future cyberpunk aesthetic alongside a plot driven by a disease called “the phage” which turns victims into non-functional computers. Because of course it does.

Anyone familiar with Zachtronics’ work will know what to expect, but Exapunks really dials things up. From the puzzles themselves – including one inspired by an early scene in the classic film Hackers – to, in a first for the format, the introduction of real though asynchronous multiplayer on top of the standard leaderboard metrics, Exapunks excels from start to oh-so-tricky finish.

The MiniWare TS100 soldering iron, meanwhile, sounds like it could be straight from Exapunks – or, given its name, TS-100: a compact temperature-controlled soldering iron with built-in screen and an open-source firmware you can hack to control everything from default operating temperature to how long before it enters power-saving “sleep mode.” While far from a perfect design – and since supplanted by the TS80, not yet available from UK stockists – the TS100 is an interesting piece of kit, with its biggest flaw being the need to use a grounding strap to avoid a potentially component-destroying floating voltage at the iron’s tip.

Finally, the project: an effort, using only off-the-shelf software tied together in a Bash shell script, to print out a schedule of the days’ tasks on my Dymo LabelWriter thermal printer. Using the code detailed in the magazine, the project pulls together everything from weather forecasts to my ongoing tasks and Google Calendar weekly schedule – along with a word of the day and, just because, a fortune cookie read out by an ASCII-art cow.

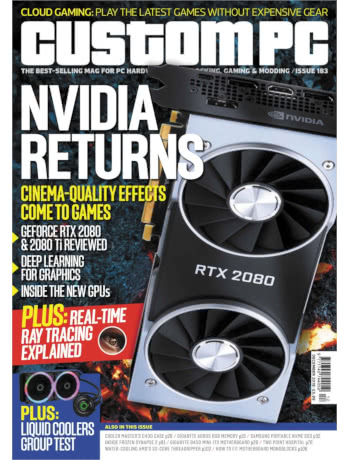

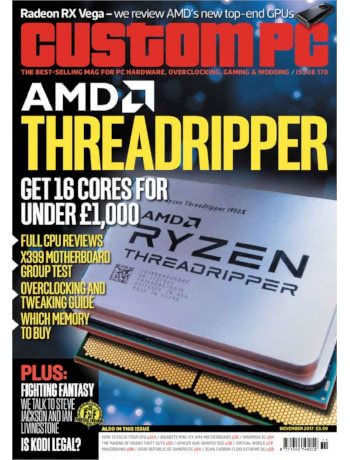

All this, and a variety of other topics, is available in the latest Custom PC Magazine on newsagent and supermarket shelves or electronically via Zinio and similar services.

This month’s Custom PC magazine has a bumper crop for fans of Hobby Tech: a four-page shoot-out of do-it-yourself handheld games consoles on top of my usual five-page column, which this time around looks at setting up

This month’s Custom PC magazine has a bumper crop for fans of Hobby Tech: a four-page shoot-out of do-it-yourself handheld games consoles on top of my usual five-page column, which this time around looks at setting up  This month’s Hobby Tech column has a particular focus on do-it-yourself handheld gaming, looking at two Arduino-compatible yet totally different kits: the

This month’s Hobby Tech column has a particular focus on do-it-yourself handheld gaming, looking at two Arduino-compatible yet totally different kits: the