First, tilde.club – which requires a little history lesson for context. In the early days of networked computing, particularly on systems based on UNIX or the later POSIX standard, users hosted shared files in their home folders – which were given the shortcut ~. Today, shared systems have given way to virtual private servers (VPSes), but tilde.club offers a reproducible platform for those who miss the early days: your own directory, with public and private areas, on a truly shared POSIX-compliant server.

As well as hosting simple websites – there’s no server-side scripting here – you can join in internal email discussions, an on-server BBS, a text-based interface for the popular Reddit social network, and even play multiplayer games, all in the comfort of your terminal. A major delay in approving accounts for the original tilde.club – five years before a volunteer took over the service and began clearing the queue – also gave rise to the tildeverse, a network of tilde.club-based servers many of which focus on particular topics of interest.

The Orange Pi 4B, by contrast, is very much not a throwback but a piece of hardware designed to sit at the cutting edge. Mimicking, with a few modifications, the layout of a Raspberry Pi single-board computer, the Orange Pi 4B offers a Rockchip RK3399 six-core processor – two high-performance cores, four low-power cores – alongside a neural processing unit (NPU) coprocessor for edge-AI acceleration. As usual, my review looks at software support, hardware performance, and thermal imaging – along with an investigation of what the NPU brings to the table.

Finally, the Pi Hut ZeroDock is a handy but sadly pricey accessory for the Raspberry Pi Zero family of single-board computers. Constructed from laser-cut acrylic, the ZeroDock houses a Pi Zero, a bundled compact solderless breadboard, and a small number of accessories like USB dongles and SD Card adapters. For those using a Pi Zero for prototyping, it’s a great tool – but at £10, twice the price of the Pi Zero board itself, it’s a little too expensive to be a must-have.

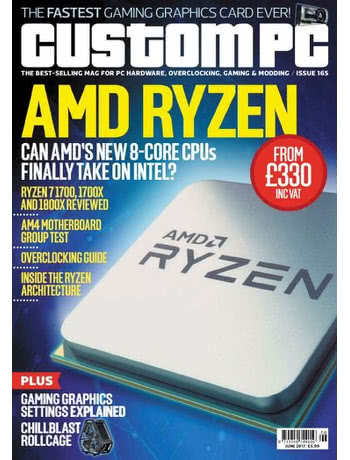

The full feature can be found on newsagent and supermarket shelves now, or purchased for global delivery from the official Custom PC website.

This month’s Linux User & Developer includes my review of Pimoroni’s

This month’s Linux User & Developer includes my review of Pimoroni’s