Written in partnership with the Micro:bit Educational Foundation, The Official BBC Micro:bit User Guide is a collaborative effort. From project editor John Sleeva who worked so tirelessly on The Raspberry Pi User Guide and has brought that same energy to The Official BBC Micro:bit User Guide and technical editor David Whale who made sure that not a semicolon was out of place to the small army of typesetters, proofreaders, copy editors, and others at publisher J. Wiley & Sons, The Official BBC Micro:bit User Guide owes its existence to far more than the person whose name appears on the cover.

Special thanks, too, must go to Zach Shelby, chief executive of the Micro:bit Educational Foundation, for his early support of the project and chief technical officer Jonny Austin who worked to see the project through from start to finish and provided exhaustive feedback to ensure it launched in the best possible condition – not to mention offering his perspective of the BBC micro:bit’s meteoric rise around the globe in the book’s foreword.

Inside the 300-page publication you’ll find step-by-step instructions from unboxing the BBC micro:bit and learning about its components to programming it in JavaScript Blocks, JavaScript, and Python, as well as practical projects which make use of its sensors, buttons, display, and radio module. You’ll have the opportunity to build everything from a wearable rain-sensing hat to a hand-held game, and links to further resources from lesson plans and community-driven content hubs to add-on hardware to expand the BBC micro:bit’s already impressive capabilities are also included.

The Official BBC Micro:bit User Guide is available now in print and electronic formats from Amazon UK, Amazon US, Kobo, Waterstones, Target, O’Reilly, WH Smith, Booktopia Australia, and direct from Wiley, while it can be ordered in at other booksellers under ISBN 978-1119386735.

For those looking for non-English resources, translations are currently in the works with a French edition confirmed for early next year and more expected to follow in due course – and if you’d like to see the book in your own native language, get in touch to discuss how to make that happen!

In this month’s Hobby Tech column I take a good long look at the BBC micro:bit, CubieTech’s latest Cubietruck Plus (Cubieboard 5) single-board computer, and a pack of Top Trumps-inspired playing cards based on vintage computers.

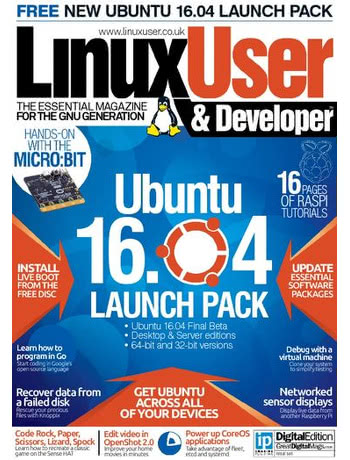

In this month’s Hobby Tech column I take a good long look at the BBC micro:bit, CubieTech’s latest Cubietruck Plus (Cubieboard 5) single-board computer, and a pack of Top Trumps-inspired playing cards based on vintage computers. For my regular review in Linux User & Developer this month I had the great pleasure to spend time with the BBC’s first serious hardware project since it teamed up with Acorn in the 80s: the BBC micro:bit.

For my regular review in Linux User & Developer this month I had the great pleasure to spend time with the BBC’s first serious hardware project since it teamed up with Acorn in the 80s: the BBC micro:bit.