Reviews are always a lot of work, but fun with it. As always, I handle the product photography myself in-house – and June’s shots have come out splendidly. The Jumperless was a little more of a challenge than usual, thanks to the presence of hard-to-capture RGB LEDs viewable only from a very precise top-down angle, but I’d like to think the results speak for themselves.

The to-review pile isn’t exhausted yet, though, so expect to see more reviews in July, along with my usual newsletters and news articles.

- The Turbo9 Reimagines Motorola’s Classic 6809 as an Open-Silicon Pipelined 16-Bit Microcontroller

- This Custom Board Adapts Lenovo’s Connector to a Real ThinkPad X1 Nano Internal USB Port

- AMD’s Ryzen AI 300 Series Packs a 50 TOPS Neural Processor for On-Device Artificial Intelligence

- Canonical Launches an Ubuntu Linux Image Optimized for the RISC-V Milk-V Mars Single-Board Computer

- “Relaxing” Memristors Could Give Future AI Systems a Major Efficiency Boost

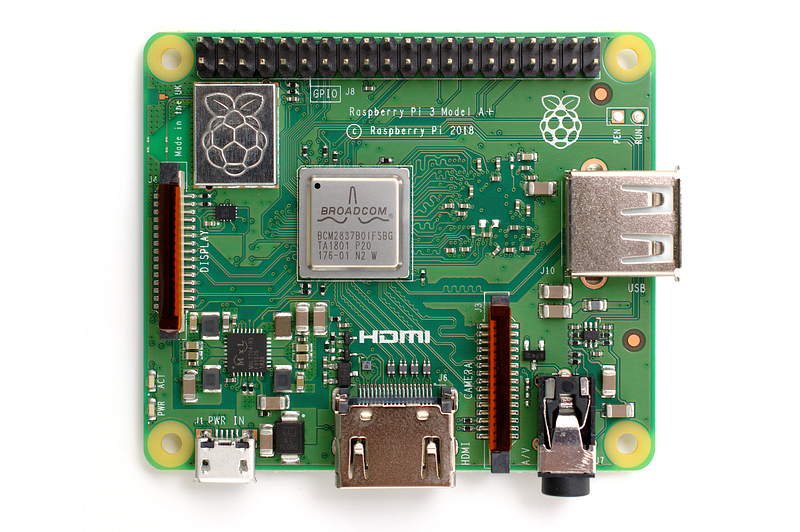

- Raspberrry Pi Teams with Dolphin Design for More Power-Efficient Chips

- Matthias “bitluni” Balwierz Creates a Tiny POV Display Controller Core in Tiny Tapeout

- Steve Markgraf’s “hsdaoh” Taps Low-Cost HDMI Capture Dongles for High-Speed Data Acquisition

- M5Stack’s CoreS3 SE Drops the Sensors, Slashes the Price

- Olimex Launches an Industrial-Grade NXP i.MX 8M Plus System-on-Module for Industrial Edge AI

- Raspberry Pi Targets Edge AI, Partners with Hailo for the Raspberry Pi AI Kit

- Dmitriy Kovalenko’s CO2nsole Offers a Slick Text-Based Interface for Environmental Monitoring

- MiKoBots’ 3D-Printable Robot Arm Features an Open Source Vision-Capable Software Stack

- Intel Promises Better AI Performance, Longer Battery Life with Upcoming “Lunar Lake” Chips

- Spec5’s Ranger is an Espressif ESP32-Powered Ready-to-Run Meshtastic Communicator

- Michael P. Turns to a Raspberry Pi Pico to Reverse Engineer These Classic Plessey Micro-LED Displays

- MNT Research Begins Shipping the Aggressively-Open Pocket Reform Netbook

- MYIR’s Latest System-on-Module Taps the AMD Artix-7 FPGA

- An Analog Network of Resistors Promises “Machine Learning Without a Processor,” Researchers Say

- DFRobot’s Indoor Ambient Energy Harvesting Kit Seeks to Skip the Battery for IoT Sensors and More

- Tommy Nielsen’s Sandwizz Turns KiCad Projects Into Wire-Free Breadboard Prototypes

- Atari’s Classic 600XL, 800XL Gain CP/M Support with This 1090 XL Zilog Z80 Expansion Board

- Arduino Cloud Gets Better Device Tracking with the New Advanced Map Widget

- Canonical’s Farshid Tavakolizadeh Turns a Raspberry Pi Into a Matter Gadget with Ubuntu Core

- Jan Dvorak’s Software-Defined Radio Is Built From a Raspberry Pi Pico — And Very Little Else

- A Tunable Metasurface Filter Could Give Future Drones Smart Infrared Crop-Monitoring Powers

- Researchers Demonstrate a Safe, Cheap, Flexible Water-Based Battery for Better Wearables

- Apple’s MacBook, iMac, and iPad Devices Get Matter-Capable Thread Radios — But Shh, It’s a Secret

- WeightAn’s Ray Marching Algorithm Turns an Arduino UNO Into a Seconds-Per-Frame 3D Renderer

- Mirko Pavleski Turns an Old Microwave Oven Into a Pocket-Friendly Spark-Shooting Tesla Coil

- Ihar Yatsevich’s Pocket-Sized WSPR Beacon Uses a SiLabs Si5351 and a Microchip ATmega328

- Classic 3D Rendering Tech Lives Again in the “World’s First 3dfx-Powered Laptop”

- Sam Hocevar’s KiCad Projects Imagine a World Where All Arduino Boards Use USB Type-C

- Oak Development Pairs a Lattice iCE40 FPGA with a Raspberry Pi RP2040 for the RPGA Feather

- These Clever Papercraft Critters Offer Robotic Movement — Through the Power of Air

- M5Stack’s Latest Espressif ESP32 Camera Module Includes Wi-Fi and Power-over-Ethernet Connectivity

- Raspberry Pi Floats on the London Stock Exchange, Brings in $211.5M to Fund Expansion and More

- Cortex Automation Aims for Plug-and-Play CNC Control with Its Teensy 4.1-Powered Neuron-1 Board

- Hozkinz Takes the Nintendo DK Bongo Controller for a Walk — Turning It Into a Portable Drum Machine

- ThingPulse’s Pendrive S3 Is an Espressif ESP32-S3-Powered Multi-Function USB Stick

- Jules Ryckebusch’s Gladys Is a Do-It-Yourself Hydrophone That Outperforms Commercial Competition

- A Human-Like Triple-Layer Sense of Touch Lets This Trash-Sorting Robot Feel Its Way to Success

- This Robotic Sniffer Dog Captures Hazardous Air Samples So You Don’t Have To

- Double-Spun PVDF Nanofibers Deliver Sensitive Flexible Sensing, Energy Harvesting for Wearables

- Flow Computing Promises a 100-Fold Performance Gain by Adding a “PPU” to a CPU

- Luca Schultz’s BikeBeamer Turns Your Wheels Into Wi-Fi-Equipped Espressif ESP32-Powered POV Displays

- Argon40’s Latest Argon ONE Case Packs a Raspberry Pi 5, M.2 NVMe Slot, and Even Analog Audio

- Jay Doscher’s Recovery Kit 2B Drops Back to the Raspberry Pi 4 for a Battery-Powered Rugged Build

- AlmaLinux 9.4, 8.10 Gain Support for the Raspberry Pi 5 Single-Board Computer

- Roman Revzin’s Crunch-E Puts an Espressif ESP32-Powered Music-Maker on Your Keychain

- Quectel Targets the Internet of Things, Industrial Networks with New Wi-Fi and Bluetooth Modules

- DeepComputing Unveils the RISC-V-Powered DC-ROMA II Laptop, Partners with Canonical on Ubuntu Port

- This Arduino-Compatible Macropad Makes Phonetic Typing Easier

- Herman Õunapuu Brings an Abandoned Printer Back From the Brink with a Raspberry Pi

- PLCs for You and Me: Hands-On with the Arduino PLC Starter Kit and Opta WiFi

- MvACon Gives Transformers Better 3D Understanding From 2D Cameras — with Minimal Overhead

- Framework Aims for Deeper Customization, Releases Framework Laptop 16 CAD Models

- Tod Kurtz’s “picotouch_bizard” Is a Business Card-Sized Pressure-Sensitive MIDI Controller

- This Student-Built Smart Bracelet Offers Round-the-Clock Monitoring for ALS, Parkinson’s Patients

- Atti Bagashov’s Giard{U}ino Energetico Delivers Water-Efficient Automated Indoor Gardening

- Franz “Fraens” Hirschböck’s 3D-Printed Bottle Labeler Takes a Pain out of Homebrew Hooch Production

- Remy van Elst Brings a Piece of Vintage Telephony Back to Life with a Simple Tone-Dialing Conversion

- LILYGO’s T-Glass Is a Low-Cost Espressif ESP32 Platform for Head-Up Display Projects

- Running Out of Desk Space? Take This Ultra-Tiny Ortholinear Keyboard for a Spin

- This Raspberry Pi Pico “Pack” Adds Two MIDI Ports Without Ballooning the Board’s Footprint

- Precor’s “Smart” Treadmills Vulnerable to Attack, IBM X-Force Researchers Warn

- Researchers Warn of Arm Memory Tagging Extension (MTE) Bypass, Vulnerabilities in the Google Pixel 8

- Sajeevan Veeriah’s New Library Aims to Ease the Use of Seeed’s LoRa-E5 with the Espressif ESP32

- Alif Unveils the Ensemble E1C, Packing a 46 GOPS AI Acceleration Alongside an Arm Cortex-M55 Core

- Sam Rossiter’s Rosmo Aims to Deliver an Easy-to-Build Robot Platform for ROS 2 and MicroBlocks

- TDK Boasts of a Hundredfold Boost in Energy Density for Its Next-Generation Solid-State Batteries

- Teledatics Prepares to Launch Its HaloMax Wi-Fi HaLow and LoraMax LoRa Comms Modules and More

- LIST Researchers Look to Test New Energy-Harvesting Technology for Small Satellites

- The postmarketOS Project Celebrates a Major Milestone as It Passes 250 Supported Devices

- Framework Announces a Partnership with DeepComputing for Its First RISC-V Mainboard

- Sipeed Univels the Lichee Book 4A, a Notebook for the “RISC-V Explorer”

- Microsoft Shrinks MakeCode to Make MicroCode, a Portable Programming Tool for the BBC micro:bit V2

- Peter Hill’s Business Card Doubles as a Handy Protoboard for Electronic Experimentation

- Adafruit’s “Code Learning” Infrared Receiver Delivers Modulated Signals for Advanced IR Projects

- Dylan Turner’s PS-OHK Is a One-Handed Keyboard with an Unusual, Single-Layer Layout

- This 3D-Printed “Reference Sugar Beet” Could Transform Crop Phenotyping — And You Can Print Your Own

- STMicroelectronics Launches the ST Edge AI Suite, Promises Inspiration and Easier Development

- The Open-Hardware RTC8088 Adds a Battery-Backed Real-Time Clock to Any IBM PC/XT or Compatible

- Sean Heber Builds an Electronic Etch A Sketch the Hard Way: With No Microcontroller

- Jeff Epler Saves Vintage Xerox 820 8″ Disks for Future Generations with an Adafruit Floppsy

- Nuvoton Unveils Its ReRAM-Packing Low-Power Arm Cortex-M23-Based M2L31 Microcontroller Range

- Joseph Naberhaus’ First Big Electronics Project Is a Doozy: Building a Computer From Discrete Logic

- Machenike’s KT84 Keyboard Packs a Low-Res “Pixel Screen” Alongside a Compact High-Res Panel

- Prototyping Magic: Hands-on with the Wire-Free Jumperless Breadboard

- Disposable NFC: Ken Shirriff Reverse Engineers the Tech Behind Montreal Métro Tickets

- Infineon’s CY8CKIT-062S2-AI Dev Kit Targets Low-Power ML and AI at the Edge

- Yeo Kheng Meng Clones the Classic Covox Speech Thing on a Chip — Thanks to Tiny Tapeout

- Stefan Wagner’s TinyStick Is a Compact Joystick/Mouse with a WCH CH32V003 RISC-V Hidden Inside

- Del Hatch’s ePiPod Offers a Raspberry Pi Zero 2 W-Powered ePaper Take on Apple’s Classic iPod

- LILYGO’s T-Encoder Pro Is a Smart Espressif ESP32-S3 Rotary Encoder and Touchscreen Display

- Clyne Sullivan’s Solar-Powered NoiseCard Lets You Know When Things Get Too Cacophonous

- Raspberry Pi Connect Gets an SSH-Like Remote Console, Expands Support to All Models

- Joel Thorstensson’s PLC Box Packs a Stack of Siemens Industrial Automation Tech in a Portable Case

- SiFive Unveils Its Fourth-Generation “Essential” RISC-V Core Range — From 32-Bit MCUs to 64-Bit CPUs

- HaiLa Partners with e-peas on a Battery-Free Wi-Fi Backscatter System Powered by Ambient Light

- Davide Orengo’s Pulse Counter Taps an ESP32-S3 and LTE Modem to Track and Report Utility Usage

- Lucas Fernando Builds a Computer Vision Model for One Task: Spotting Naruto Hand Signs

- Is Cooking Your Motherboard a Surefire Fix for Faulty Electronics? Hold the Oven, Says iFixit

- This Transparent Edge-Lit Seven-Segment Display Is Clearly a Great Build

- This Metamaterial Captures and Boosts Tiny Vibrations, Delivering Electricity for the IoT and More

- GOWIN Goes High-Throughput with Its Arora-V GW5AT-15 FPGA, Targets 4k Video Applications

- Olimex’s Neo6502 Goes Portable as the Neo6502PC, a Compact Open-Hardware Tablet Throwback

- Oasa’s R1 Robot Mower Combines a Classic Reel Cutter with Bleeding-Edge Autonomous Smarts

- Josh Fox Wants to Put Computer Vision to Work Making Cycling Safer with the Survue Smart Light

- These Maple Seed-Inspired Twirling Robots Can Deliver Sensor Packages to the Most Remote Locations

- PINE64 Becomes the Latest to Adopt the Unusual Sophgo SG2000 Multi-Architecture Chip in Its Oz64

- This Kirigami-Inspired Mechanical Computer Needs No Electronics, Only Plastic Blocks and Tape

- Proposed Linux Kernel Patch Could Boost Raspberry Pi 5 Performance by Up to 18 Percent

- Will Whang’s FourThirdsEye Puts a Sony IMX294 Sensor on Your Raspberry Pi 5 or Compute Module 4

- Auterion’s New Skynode S is an Ultra-Compact Autopilot Platform with On-Device AI Smarts

- Andy Geppert’s Business Card Is Making Moves — As It’s a Literal Brushless Motor

- Alley Cat’s “Alley Chat Pocket HT” Brings Back the Pager with LoRa and Meshtastic Technology

- Quectel’s FLM263D Is a RISC-V Wi-Fi and Bluetooth Low Energy Module Targeting Matter Projects

- Wavelet Lab Picks Lime Micro’s LMS7002M for its High-Performance 8×8 xMASS SDR

- FOSSi Foundation El Correo Libre Newsletter Issue 75

- MyriadRF OTA Newsletter: Wavelet Lab Unveils the xMASS SDR, LimeNET Micro 2.0 Orders Open, a Raspberry Pi Pico SDR, and More