My interest in the Blink ecosystem is not purely academic. Having recently purchased a new house, I saw the opportunity to deploy a cost-effective camera system while documenting the process for Hobby Tech – and I’m pleased to report that Blink, which is entirely battery-driven bar a mains-powered “Sync Module, made things easy. The hardware was initially photographed in my studio then installed on-site with additional imagery captured, before being tested over a period of weeks to iron out teething problems.

The Raspberry Pi Pico W, meanwhile, is a near-identical clone of the Raspberry Pi Pico microcontroller board – but this time it’s brought a radio along for the ride. At the time of writing, only Wi-Fi was available – with Bluetooth present in hardware but not yet enabled in the firmware – but that’s enough to vastly expand the possibilities for projects driven by the Raspberry Pi Pico and its RP2040 microcontroller. Better still, the price has been kept low: at £6 including VAT, it’s near-impossible not to recommend the Raspberry Pi Pico W.

Finally, I reviewed the PolarFire SoC Icicle Kit back in Issue 224 – and one of my biggest complaints was with the pre-installed Linux distribution, which was extremely spartan and not a little buggy. It may have only been five months since that review was published, but things have change for the better – and to prove it I used Microchip’s documentation and Yocto Linux board support package (BSP) to build a much more polished Linux operating system for the board.

All this and more is available at your nearest newsagent or supermarket, online with global delivery, or as a free download on the official website.

In this month’s Hobby Tech column I take a good long look at the BBC micro:bit, CubieTech’s latest Cubietruck Plus (Cubieboard 5) single-board computer, and a pack of Top Trumps-inspired playing cards based on vintage computers.

In this month’s Hobby Tech column I take a good long look at the BBC micro:bit, CubieTech’s latest Cubietruck Plus (Cubieboard 5) single-board computer, and a pack of Top Trumps-inspired playing cards based on vintage computers. For my regular review in Linux User & Developer this month I had the great pleasure to spend time with the BBC’s first serious hardware project since it teamed up with Acorn in the 80s: the BBC micro:bit.

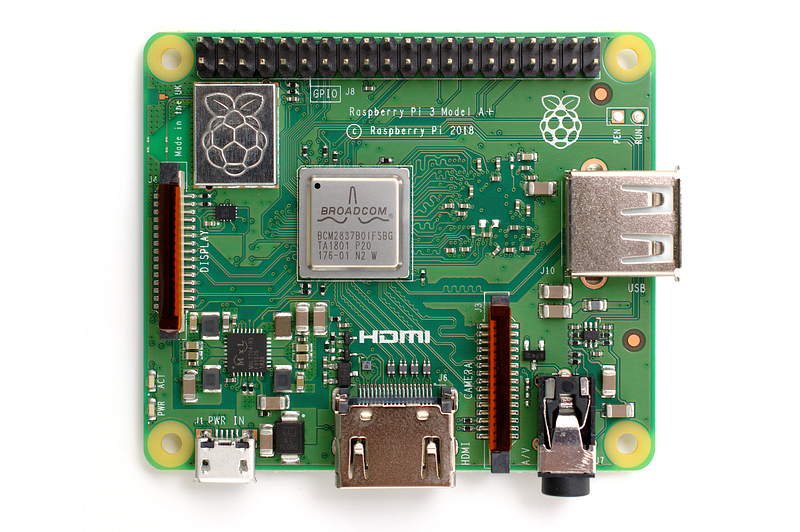

For my regular review in Linux User & Developer this month I had the great pleasure to spend time with the BBC’s first serious hardware project since it teamed up with Acorn in the 80s: the BBC micro:bit. My review for this month’s Linux User & Developer magazine is of a device I’ve been playing with for a while now: the Raspberry Pi 3, the first single-board computer from the Raspberry Pi Foundation to include a 64-bit CPU and integrated radio chip.

My review for this month’s Linux User & Developer magazine is of a device I’ve been playing with for a while now: the Raspberry Pi 3, the first single-board computer from the Raspberry Pi Foundation to include a 64-bit CPU and integrated radio chip.