This month’s Linux User & Developer includes a rare laptop review, my first for the magazine since the Hewlett Packard 455 G3 in Issue 158, courtesy Newcastle-based Nimbusoft: the Aurora.

This month’s Linux User & Developer includes a rare laptop review, my first for the magazine since the Hewlett Packard 455 G3 in Issue 158, courtesy Newcastle-based Nimbusoft: the Aurora.

The Nimbusoft Aurora is the Ultrabook entry in a range of products the startup company is offering for sale, designed to offer portability at a reasonable price. Based on a chassis from original design manufacturer (ODM) Topstar, the Aurora can be tweaked at the time of ordering: the review sample sent across came with an SSD instead of a hard drive and an upgraded wireless card, both of which were reflected in the slightly raised price in the review.

The hardware’s not the star here, though: Nimbusoft is one of the only companies in the UK not only offering Linux as a pre-installed option on its devices but offering Linux exclusively. You’ll find no option to buy Windows on the Nimbusoft website, nor a PC Specialist-style option to buy the devices without an operating system installed; instead, all laptops come equipped with Ubuntu 16.04.1 LTS and you choice of officially-supported desktop environments.

As a Linux user myself, it’s a great feeling knowing that the laptop you’re firing up is fully supported and won’t run into any strange errors as a result of not-quite-ready wireless drivers or a badly-supported LCD backlight circuit. Accordingly, I was thrilled when the Aurora booted up in to an absolutely stock Ubuntu install with no bloat or branding, ready for me to give the device a name and create my user account.

While Nimbusoft may not offer Windows machines, the same can’t be said for other Topstar customers; as a result, there’s the usual workaround for the Super key being emblazoned with Microsoft’s Windows logo: a sticker, with a range of replacement logos available at the time of purchase or the key being left stock if you’d prefer. The same can’t be said of the Internet Explorer logo on one of the shortcut keys, though, and I was disappointed that this didn’t trigger Firefox when pressed – but that, the relatively poor keyboard, and a slightly sub-par battery life of five hours, were pretty much the only negative points I encountered during the review.

If you’d like to read my full analysis from a Linux user’s perspective, Issue 173 is on shelves now and also available electronically from Zinio and similar distribution services.

It’s always nice to see your name in a new publication, and doubly so when it’s the magazine’s very first issue, so imagine my pleasure when Future Publishing’s Create Magazine hit shelves this week and brought my feature on building your own Linux PC along for the ride.

It’s always nice to see your name in a new publication, and doubly so when it’s the magazine’s very first issue, so imagine my pleasure when Future Publishing’s Create Magazine hit shelves this week and brought my feature on building your own Linux PC along for the ride. Readers of this latest issue of Imagine Publishing’s Linux User & Developer will find my review of the surprisingly capable Nextcloud Box, a bare-bones network attached storage (NAS) system based around a Raspberry Pi 2.

Readers of this latest issue of Imagine Publishing’s Linux User & Developer will find my review of the surprisingly capable Nextcloud Box, a bare-bones network attached storage (NAS) system based around a Raspberry Pi 2. In this latest issue of Imagine Publishing’s popular Linux User & Developer you’ll find my two-page review of NextThingCo’s clever CHIP single-board computer and PocketCHIP hand-held computer, combined into a single piece thanks to their similarity.

In this latest issue of Imagine Publishing’s popular Linux User & Developer you’ll find my two-page review of NextThingCo’s clever CHIP single-board computer and PocketCHIP hand-held computer, combined into a single piece thanks to their similarity. This month’s Linux User & Developer includes my review of Pimoroni’s

This month’s Linux User & Developer includes my review of Pimoroni’s  This month’s Linux User & Developer includes a review of the Cubietruck Plus – also known as the Cubieboard 5 – I previously reviewed in

This month’s Linux User & Developer includes a review of the Cubietruck Plus – also known as the Cubieboard 5 – I previously reviewed in  For my regular review in Linux User & Developer this month I had the great pleasure to spend time with the BBC’s first serious hardware project since it teamed up with Acorn in the 80s: the BBC micro:bit.

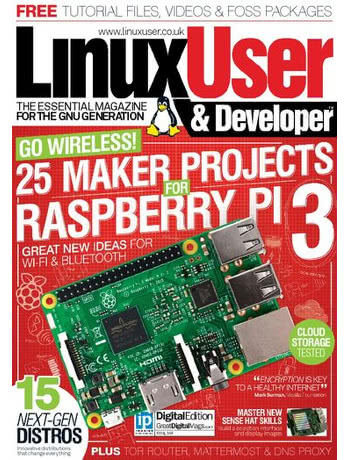

For my regular review in Linux User & Developer this month I had the great pleasure to spend time with the BBC’s first serious hardware project since it teamed up with Acorn in the 80s: the BBC micro:bit. My review for this month’s Linux User & Developer magazine is of a device I’ve been playing with for a while now: the Raspberry Pi 3, the first single-board computer from the Raspberry Pi Foundation to include a 64-bit CPU and integrated radio chip.

My review for this month’s Linux User & Developer magazine is of a device I’ve been playing with for a while now: the Raspberry Pi 3, the first single-board computer from the Raspberry Pi Foundation to include a 64-bit CPU and integrated radio chip.