That this month’s Hobby Tech column includes the review of a single-board computer should come as no surprise; that it’s a Windows 10 machine, though, certainly shakes things up a bit – as do a guest appearance by my trusty Cambridge Computers Z88 and an interview with Indiegogo’s Joel Hughes on the topic of crowdfunding.

That this month’s Hobby Tech column includes the review of a single-board computer should come as no surprise; that it’s a Windows 10 machine, though, certainly shakes things up a bit – as do a guest appearance by my trusty Cambridge Computers Z88 and an interview with Indiegogo’s Joel Hughes on the topic of crowdfunding.

The DFRobot LattePanda isn’t a new device, but it’s new to me. While I’ve probably reviewed more single-board computers than any other device category – and written the book on more than one – the LattePanda stands out from the crowd for two reasons: it uses an Intel Atom processor with considerable grunt, and it runs Microsoft’s Windows 10 Home operating system. Add in to that an on-board Arduino-compatible microcontroller and you’ve got a very interesting system indeed – and one which only got more interesting when I popped it under the thermal camera.

My interview with Indegogo’s Joel Hughes, meanwhile, took place in the spacious hall of Copenhagen’s former meat-packing district as part of the TechBBQ event. “We want to democratise funding as much as possible and level the playing field for great ideas,” he told me, before I threw a few tricky questions about some high-profile campaigns that had perhaps fallen short of greatness – or even mediocrity. “I don’t feel, the majority of the time, that it’s malicious,” he claimed on the topic of campaign operators who fail to keep their backers in the loop on post-fundraising progress. “I think they’re busy doing their own thing and almost forget about the comment section a little.”

Finally, the Cambridge Computers Z88. Although it’s been in my possession for many years, has a bag-friendly A4 footprint, and runs for a full day’s work on a set of double-A batteries, I’ve shied away from using Uncle Clive’s portable for serious work owing to the difficulties in actually getting documents off its internal memory and onto something more modern. The purchase of a PC Link II kit and some clever open-source software, though, has solved the problem, and if you see me out and about at events don’t be surprised if I’m taking notes on a rubber-keyed classic.

All this, plus a bunch of other stuff, is available at your nearest newsagent, supermarket, or digitally via Zinio and similar distribution services.

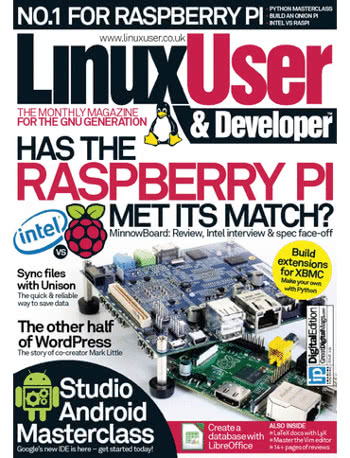

The cover of this month’s Linux User & Developer Magazine highlights two of my latest features: a review of the Intel MinnowBoard and an interview with its evangelist Scott Garman. The direct comparison to the far cheaper Raspberry Pi, just to clarify, was an editorial decision in which I had no part.

The cover of this month’s Linux User & Developer Magazine highlights two of my latest features: a review of the Intel MinnowBoard and an interview with its evangelist Scott Garman. The direct comparison to the far cheaper Raspberry Pi, just to clarify, was an editorial decision in which I had no part.